|

| Andrea Dworkin |

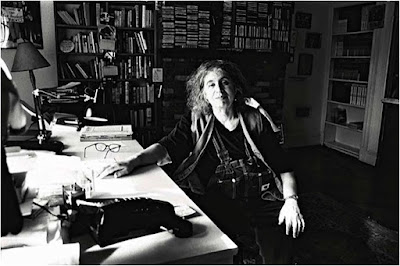

Most people are at least familiar with Andrea Dworkin as feminist icon, with her massive physical bulk, her impassioned rhetoric, and her trademark lesbian-identified overalls. Fewer have read her books. In their time, the books were considered ground-breaking and even true. Feminist author Ariel Levy has called Dworkin a “savior goddess” and the “evangelical, untouchable preacher for the oppressed” (Intercourse, xix). Today Dworkin’s unhinged hatred of men seems bombastic and disingenuous. Yet her impact on North American feminist culture is undeniable.

No feminist did more to outline and consolidate the modern feminist understanding of sex than Dworkin (1946-2005), who wrote on the subject obsessively and with unparalleled fervid authority in books with titles such as Woman Hating (1974). Like other radical feminists, Dworkin fulminated against rape, pornography, and prostitution—joining forces in the early 1980s with law professor Catharine MacKinnon to draft anti-pornography legislation—but her special focus was the degradation for women of sex itself, everyday sex, the commonly accepted, normalized indignity that men allegedly inflict on women. Sex, she believed, embodied nothing less than male hatred. “Intercourse is the pure, sterile, formal expression of men’s contempt for women” (p. 175). This is the thesis of her most representative book Intercourse, published in 1987 when Dworkin was 41 years old.

Intercourse set out to illuminate, through select readings of literary texts, what Dworkin believed to be the constant of male culture, the “hatred of women, unexplained, undiagnosed, mostly unacknowledged, that pervades sexual practice and sexual passion” (175-76). The phrase she most often used in the book to refer to intercourse was “the fuck,” meant to signify the dehumanization that normal intercourse supposedly involved. Dworkin nominated herself the expert on male contempt for women because she had been, as she claimed, its victim. “Specifically, am I saying that I know more than men about fucking?” she asked defiantly in the Preface to the book, and answered, “Yes, I am. Not just different: more and better, deeper and wider, the way anyone used knows the user” (xxxi).

Though she also claimed in her combative Preface that the book “does not say that all men are rapists or that all intercourse is rape” (xxxii)—she does, as I will show, essentially say that, if not in quite those words. As she asserted only a page after the denial, “Intercourse [the book] conveys […] what it means that men—and now boys—feel entitled to come into the privacy of a woman’s body in a context of inequality” (xxxiv). In another segment, she clarified that most, even the vast majority of, men are sexually abusive. Men objected to feminist critique of pornography and prostitution because, she alleged, “[…] so many men use these ignoble routes of access and domination to get laid,” that “without them the number of fucks would so significantly decrease that men might nearly be chaste” (p. 61). Men who objected to her arguments about the omnipresence of exploitation were themselves abusers who didn’t like the thought of their exploitation being curtailed.

This was Dworkin: bombastic, hyperbolic, incandescent with a rage that did not excuse her smearing of all men even if her accounts of sexual abuse at men’s hands were true and unadorned. Late in life, Dworkin made bizarre allegations about having been raped in a Paris hotel room that even her most devoted admirers found very difficult to believe. Ultimately, no one knows the truth of Dworkin’s many alleged violations, which were the basis for all she wrote.

Dworkin said she had been molested or raped at around 9 years of age, later abused by New York City prison doctors at age 18 after her arrest during a Vietnam War protest, and then badly beaten many times by a man she had married in Amsterdam in the early 1970s.

Though she escaped this man and carried on a life of writing and advocacy in the United States, during which time she became closely associated with feminist leaders such as Susan Brownmiller, Gloria Steinem, and Catharine MacKinnon, Dworkin’s feminist advocacy was always distinguished from these other leaders by its unmitigated, condemnation of men.

And to this day, the vast majority of feminist leaders are undisturbed by Dworkin’s bigotry, justifying it as understandable, even necessary and helpful. “People who […] raised their eyebrows at her supposed extremism or her intransigence or her fire took secret glee from that,” Robin Morgan stated, adding that, like Malcolm X, Dworkin’s was “the militant voice, […] the voice that would dare say what nobody else was saying . . . and it can’t help but say it because it is speaking out of such incredible personal pain” (qtd in Levy, pp. xix-xx). That Dworkin had pain seems undeniable—she was eating to fill some kind of emotional void—but whether its sources were as she claimed has never been ascertained.

|

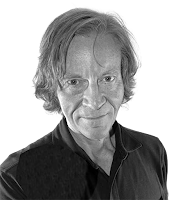

| John Stoltenberg |

As an antipornography activist, Stoltenberg used to offer college workshops in which he would invite men to assume the positions in which women were photographed for pornography in order to make them feel the women’s humiliation (xxiii). The very fact of Stoltenberg’s masculinity-denying adoration for his uncompromising wife undermines much of what Dworkin claimed in her writings about the abusive nature of men, but that hasn’t diminished her reputation as a radical truth-teller with her followers.

In 2006, Ariel Levy claimed in the Foreword to the reissue of Intercourse that “Dworkin’s profound and unique legacy was to examine the meaning of the act most of us take to be fundamental to sex […]” and hedged that, “If you disagree with her answers, you may still find yourself indebted to her for helping you discover your own” (xv). This is Levy’s attempt to distance herself from Dworkin’s despicable anti-male generalizations while still praising the author’s alleged insights. But Dworkin never examined anything per se: she pontificated, judged, and damned from her self-chosen pulpit as the excoriating prophet of male sin, and her encouragement to thousands of other women to hate with equal passion remains her destructive legacy, one that is as unhelpful as it is patently untrue.

In the book Intercourse, Dworkin broke every rule of responsible literary criticism and cultural analysis, reading works of literature as if they directly reflected the author’s mind; if the author described a character who hated women, that must mean that the author hated women and endorsed such hatred. But if some of the works seemed to have pro-woman sympathies, that didn’t complicate Dworkin’s argument. From the Dworkin point of view, a male author who wrote critically of women was a misogynist, while a male author who wrote critically of men was merely a realist—though likely a misogynist too. Women were never admitted to be capable of sadism, cruelty, indifference to suffering, or narcissism. “Women have a vision of love that includes men as human too” (p. 162). Men had only the choice they seemed unwilling to make: “When will they choose not to despise us?” (p. 177), she asked.

Throughout the book Dworkin always chose the most reductive explanations possible for male attitudes and responses, as for example when she claimed that “Most women are not distinct, private individuals to most men; and so the fuck tends toward the class assertion of dominance. Women live inside this reality of being owned and being fucked” (p. 83). And, “[T]he hatred of women is a source of sexual pleasure for men in its own right” (p. 175). And so on and on.

The writing is at times incisive, but more often erratic, highly repetitive, and feverish, with chains of assertions carried along by Dworkin’s exultant, self-perpetuating anger. It is testimony to the delusional bitterness of feminist ideology that such ranting has been taken as insight—and one need only read the eulogies upon her death and the many commendations of her brilliance to see how many feminists are still unashamed to admire even while denying Dworkin’s openly expressed hatred.

At times in the book, Dworkin suggested that a sexuality of loving equality between men and women might be possible. But the only concrete example she was willing to provide was self-admittedly not equal but female-supremacist: it was a model imagined by 19th century American feminist Victoria Woodhull, whom she called “the great advocate of the female-first model of intercourse” for whom “women had a natural right—a right that inhered in the nature of intercourse itself—to be entirely self-determining, the controlling and dominating partner, the one whose desire determined the event, the one who both initiates and is the final authority on what the sex is and will be” (p. 171).

Here we see the deliberately asymmetrical logic of feminist rights advocacy: only when women control sexuality entirely—even controlling its meaning as sex or rape—can it approach “equality.” At other times in the book (see especially p. 156-158), Dworkin seemed to assert that the physical reality of intercourse—which involved violating the integrity of the female body—made it innately unequal, and therefore always to some degree an enactment of male power over women.

In 1983, 500 men gathered in St. Paul, Minnesota, to hear Dworkin give a speech at the Midwest Regional Conference of the National Organization for Changing Men (now the National Organization for Men Against Sexism). The speech was called “I Want a Twenty-Four-Hour Truce During Which There is No Rape.” As the men might have expected, Dworkin pulled no punches, granted them no exemptions as pro-feminist men who wanted to “change” men. She ripped into them, telling them that if they thought the problem of misogyny and abuse and exploitation was “out there,” they were wrong. It was “in you,” she told them. “The pimps and the warmongers speak for you” (“I Want a Twenty-Four-Hour Truce,” p. 165). And she told them that as men they were full of “contempt and hostility in [their] attitudes towards women and children” (p. 166).

She harangued them, derided them, and threatened them that if they couldn’t end rape at least for one day they could never claim to believe in equality or care about women. They had not done it because they clearly did not really want to. And therefore, she said, “The shame of men in front of women [was] an appropriate response both to what men do and to what men do not do” (170). Until they could “end rape” and call off their side, as she called it, their shame and guilt “were not good enough” (p. 170).

That was what Dworkin had to give to men, shame and guilt, endless denunciation, and the impossible task of ending rape, which she claimed was “so little” (171) to ask.

They could also live like her gay husband, writing articles and books about how they had renounced being men and encouraging other men to feel shame. And even then, they would have to look every day, metaphorically, at least, as Stoltenberg had actually looked, at a poster in his home that said “Dead men don’t rape” (xxii), the poster that Dworkin had placed above the desk where she wrote her screeds. No wonder Stoltenberg could not bear to be a man. Even renouncing manhood was not enough for Andrea Dworkin and the legions of feminists she continues to inspire.

Janice Fiamengo

No comments:

Post a Comment