Feminism’s origin story about the right to vote is full of inaccuracies and outright myths.

Popular perception has it that over one hundred years ago, women fought long and hard for their rights, especially the right to vote, gained after the First World War. To gain this right, so the mythology goes, they had to battle widespread misogynistic contempt from privileged men.

The struggle for the vote as a feminist origin story thus encapsulates the righteousness of the movement and the blatant injustice of patriarchal societies.

But an examination of the history of the extension of the franchise shows that both the villains and the heroines of this story are false constructs used to whip up retaliatory anger at men and belief in the heroic legitimacy of feminism.

But what is important to recognize is that the opposition to women’s voting rights was not based on dislike of women or indifference to their well-being—quite the contrary. Whereas feminist leaders agreed in their highly negative assessments of men, the anti-suffragists were not in general anti-woman, and many of those who campaigned against female suffrage were active in the promotion of women’s health, their rights in marriage, and their access to higher education. Opposition to female suffrage was generally based not on misogyny but on a specific vision of the social good.

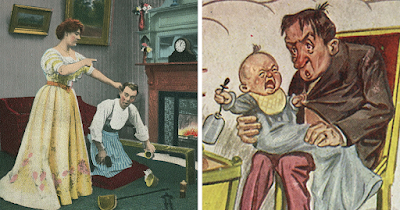

|

| Anti-suffrage cartoons |

Before turning to the views of those who opposed women’s suffrage, it’s worth considering that voting rights would in time almost certainly have been extended to women even without the massive displays of feminine fury and wounded self-love that suffrage activists, especially the militant suffragettes, presented to the English-speaking world.

The nineteenth century was a period of sweeping democratic reform that saw an extensive series of parliamentary changes in Britain that progressively extended voting rights that had been originally restricted to upper class men alone. Until the later nineteenth century, the vast majority of British men lacked the right to vote; and it’s difficult to believe that the vote wouldn’t have been given to women in time as part of the expansion of democracy. That feminists then and now almost never acknowledge the presence of voteless men (in Britain and elsewhere) should on its own completely invalidate their myth-making.

Briefly: voting rights were first extended in 1832, then again in 1867, and again in 1884. The 1832 Reform Act gave the vote to about one in six property-owning adult men. The 1867 Act extended the vote to working-class men in urban areas; and the 1884 Act gave the vote to rural working-class men. In all cases, income and property qualifications limited the extensions, with the result that about 40% of British men still did not have the right to vote in the period after 1884 and through the First World War, the very time when feminist women were making their angry demands.

The argument against extending the vote to women was most often made on the assumption that women were in general less suited to politics by temperament.

At a time when most women were occupied in the domestic realm, often pregnant, often caring for children, and dealing with complex households, it was doubted that women had the capacity to understand or even care about politics. One anti-suffragist observed of the women in her district that “Many … simply go on from day to day without taking any part in the wider life outside them, without being in the least interested in any public question.”Such an assumption, though irritating to suffrage activists (who were mostly ambitious, intellectual women of the upper class) did not signal lack of appreciation for what women did contribute to society as mothers, helpmeets, educators, authors, healers, care-givers, or community activists. Women had always been involved, and encouraged to be so, in local and municipal elections, and in charity work.

But in general, anti-suffragists believed that women and men were happiest, and society functioned best, when there was a complementary division of labor with women focused mainly on the home front while men acted in the larger world. Historian Brian Harrison summarizes that “The precariousness of life, the absence of welfare facilities, the frequency of childbearing, the complexity of housekeeping, the central importance of domestic economy in the literal sense—these were all factors which forced husbands and wives into mutual dependence” (Harrison, 68).

According to the anti-suffrage view, it was simply not true that women lacked political representation without the national franchise. On the contrary, women’s interests were vigorously pressed by the men in their families and by male politicians. Liberal party member and British ambassador to Washington James Bryce contended that “There can be no more baseless assumption than that the polling-booth is the main source of influence in politics. Women already enjoy greater influence in other ways, both public and private, than the franchise would give them” (qtd. in Harrison 81). Some argued that women had more influence precisely because they weren’t bound by party loyalties and their advocacy was thus seen as non-partisan.

Throughout the nineteenth century, the subjects on which women did agitate for reform—including women’s higher education, changes to divorce law and child custody, women’s property rights, age of consent—saw an all-male Parliament quick to act. Harrison notes, “It is difficult to think of reforms for which late Victorian women energetically campaigned and which they were not granted” (73).

What was sometimes called the “separate spheres” arrangement was promoted by anti-suffragists as most likely to uphold women’s well-being.

Anti-suffragists believed that politics was ultimately, and should remain, a male contest because the ballot was a metaphorical substitute for the ability and requirement to use physical force, if necessary, when politics failed; to extend the ballot to those without the obligation or ability to fight, was to introduce a falseness into the political system that would ultimately weaken whatever nation implemented it.

If they were wrong, it was not because they hated women. Some of them, on the contrary, worshipped women and wanted to protect them from the corrosive effects of public life.

As we know, such arguments did not win the day.

Neither, though, did the angry demonstrations of the pro-suffrage forces, which were never popular with a majority of the public and may in fact have delayed the granting of the vote by showcasing the hysterical vehemence of many, especially the suffragettes who smashed windows, set off bombs, and physically attacked parliamentarians and police officers.

Feminist Wilma Meikle in her 1917 book Towards a Sane Feminism proposed that much pre-war feminist agitation had been inspired by little more than lust for public celebrity and pointless rage. “Let us while there is still time for repentance humbly and with tears confess that all that was done and undone by pre-war feminists was nothing but a prodigious crop of feminine wild oats” (14).

Somewhat ironically, it was the First World War that decided the matter of the suffrage. Women’s service on the home front—their work in munitions factories and farms—changed public attitudes toward women, and a 1917 vote passed easily in the British Parliament to extend the franchise to servicemen who had previously been voteless, and to women aged 30 and above.

The war might have confirmed the anti-suffrage argument that physical force was still a factor in world affairs, and that, unable to fight, women should not be able to direct national decisions. But it didn’t.

Women thus won the right to vote on the backs of hundreds of thousands of men dead in the trenches of Europe.

Feminist activists like Emmeline Pankhurst and her daughters, now considered the great heroines of the noble suffrage struggle, contributed little or nothing to the victory.

And although it is now difficult to imagine a world without women voting in national elections, it is at least as difficult to outright dismiss the anti-suffragists’ concerns.

A female electorate has made politics increasingly emotion-based, with an ever-expanding state bureaucracy catering largely to women’s social concerns, fears, and easily-triggered outrage.

One hundred years after women began voting, research has repeatedly found that men express far more knowledge about and interest in political matters. A 2019 article about the gender gap in Britain reported a 20-point gap in expressed political interest amongst 15-year-olds and a 30-point gap amongst 25-year-olds.

A Pew Research Poll of Americans found women consulting newspapers for stories primarily about “weather, health and safety, natural disasters, and tabloid news.” Men were more interested in “international affairs, Washington news, and sports.” According to another report that criticized newspapers for failing to attract female readers, women prefer local stories, accessible graphics, and an engrossing narrative rather than fact-based news. The stereotypes that suffrage activists raged against have turned out to be mostly true.

What is perhaps most interesting about the debates concerning women’s voting rights is that they occurred at a time when it was still possible to discuss what was best for society from a perspective that included everyone: men, women, and children—not just women. One of the things that woman suffrage achieved was to make it nearly impossible, finally, to talk about any ‘good’ other than a feminist one.

Janice Fiamengo

No comments:

Post a Comment