Decades of feminist theorizing have stressed the dark side of male sexual desire, its violence, its alleged objectification of women, and its alleged infliction of indignities. When Germaine Greer turned her attention to female sexuality, in a book about female pederasty, or sex with boys, she was unashamedly celebratory.

|

| Germaine Greer |

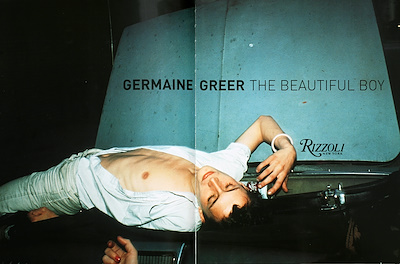

In 2003, well-known Australian feminist Germaine Greer published The Beautiful Boy, a picture book with commentary that had as one of its stated purposes to encourage women to reclaim their pleasure in looking at boys’ naked bodies. The book also included approving commentary about sexual relationships between adult women and pubescent boys.

Greer’s argument concerning representations of nude boys was that while it was generally acknowledged that young women’s bodies are beautiful, and that men enjoy looking at them, almost no one acknowledges the fact of male beauty. Greer claimed that such beauty was found not in mature men but almost exclusively in boys, and her book documents and encourages the sexualizing of boys’ bodies.

She moved quickly in the book to specify the exact age and stage of adolescence that represented the height of male beauty, acknowledging that “This window of opportunity is not only narrow, it is mostly illegal.” Claiming without any evidence or argument that mature men are not beautiful, Greer alleged that a boy is most attractive when young: “He has to be old enough to be capable of sexual response but not yet old enough to shave.”

And she continued enthusiastically: “The male human is beautiful when his cheeks are still smooth, his body hairless, his head full-maned, his eyes clear, his manner shy and his belly flat” (p. 7). She was 64 years old when she published the book and was obviously expressing her own personal preferences.

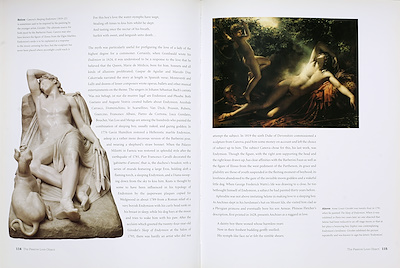

Greer’s picture book argued a part-art-historical and part-ideological thesis, seeking to demonstrate, through numerous representations of classical Greek and Roman statuary as well as Renaissance and later paintings by European masters, that until a few hundred years ago, artists were well aware of the aesthetic and erotic power of the boy nude. Furthermore, she said, “Women too have known it and know it still [i.e. that boys are beautiful]. Girls and grandmothers are both susceptible to the short-lived charm of boys, women who are looking for a father for their children less so” (p. 7).

The boy nude was commonplace in art to embody masculine values, and it was only when “As women joined the viewing public […] toward the end of the eighteenth century, both masculinity and sensuality drained away from depictions of the male nude” (p. 10). “Part of the purpose this book,” she wrote, “is to advance women’s reclamation of their capacity for and right to visual pleasure. If we but lift our eyes to the beautiful images of young men that stand all about us, there is a world of complex and civilized pleasure to be had” (p. 11).

How nice for women to indulge their “complex and civilized pleasure.” One wonders whether men have a right to similar visual pleasures. Do men’s desires also deserve to be celebrated? In the typically doubled-standards of feminist proselytizing, Greer never does say. Perhaps she believed that men’s pleasures are so well entrenched in the culture as to be not worth defending.

Greer’s book is emphatically about women as viewers, women as desiring subjects, and although she writes with compassion and awareness of the vulnerabilities of boys and their lives throughout history, her focus is on the liberatory potential of female desire.

She writes approvingly of sexual relationships as depicted in literature between boys of 15 and women twice their age. Speaking of one example, she says, “If there is an element of child abuse in [the woman’s] seduction of the boy, it is that no love he ever experienced afterward could match either the comfort or the intensity of this relationship, in which the boy was never in control but so quick to regain his erection that it didn’t matter” (p. 77). Greer pours out scorn on 21st century moralizers who see sex between adolescent boys and older women as abuse, echoing Freudian disciple and psychoanalyst Melanie Klein in asking of such relationships, “Who is seducing whom?” In other words, Greer, like Klein, assumes that in such a scenario, the boy is at least as responsible for seduction as the woman, an allegation, it hardly needs to be said, that would not be possible to be made about a young girl allegedly seducing a mature man.

Germaine Greer is a prolific author who has always been an eccentric, controversial feminist, a campaigner for sexual liberation rather than for women’s rights, a belligerent contrarian who seems to enjoy saying outrageous things, and a renegade who admitted to not liking women very much.

Her major book, The Female Eunuch, published in 1970 during the heyday of the Second Wave of feminism, has sold millions of copies and been translated into dozens of languages.

For having written that book, Greer was called the “Saucy feminist that even men like,” and her argument in The Female Eunuch has been described, rather disapprovingly, as libertarian rather than revolutionary in encouraging women to look inside themselves to discover who they are rather than agitating as a collective for specific social rights.

One feminist review of The Female Eunuch castigated Greer for daring to blame women for much of their own misery, and lamented what she saw as the “lack of ‘sisterhood’” Greer showed.

Now in her early 80s, Greer remains a lightning rod for criticism, most recently because of her outspoken refusal to recognize trans women as women.

Greer’s unorthodoxy is evident in The Beautiful Boy, which never claims that boys are privileged, never laments that boys have an easier time of it than girls, as we have too often seen amongst feminist ideologues.

While prone to many sweeping assertions of the type inevitably open to criticism by specialists, she is always at least aware of the humanity of boys, and certainly of the hardships and cruel treatment boys have had to endure through history. In that sense, this is not a particularly feminist book, and it even may be said to be a remarkable book for a feminist woman to have written, one that sees boys as fully human, and not as little oppressors in waiting.

Be that as it may, Greer’s rampant sexualizing of boys, which is overt and unapologetic throughout, makes for uneasy reading and remains quite shocking even twenty years after the book’s first publication. Greer is especially interested in representations of boys as “passive love objects,” which is the title of her fifth chapter. Boys who are immobilized and passive in sleep are the perfect erotic objects, she asserts, open to the woman’s desiring contemplation and advances. She describes the ideal scene as follows:

“As he sleeps, amorous eyes may feast upon his beauty; when those eyes belong to a woman, she is for once powerful and dominant, free to feed her own desire as slowly and deeply as she wishes, building her own excitement and deliciously delaying any consummation, as mother-like she takes pains not to wake the sleeping beauty” (p. 105).

What is striking here, as throughout the book, is the entirely positive valence that words like desire, power, and even dominance assume when their reference is to a woman sexually desiring—and fondling, it seems—a sleeping boy. No apology is made for the emphasis on the boy’s passivity and powerlessness. Greer does not pause even for a moment to worry over the lack of consent clearly implied in the older woman’s taking of pleasure with a sleeping or only half-awake boy.

And in this emphasis, Greer is squarely part of the feminist tradition. Female sexuality is almost invariably represented by feminists as a force for good or at least incapable of causing harm. For Greer in particular it is pure, motherly, and uplifting, both for the female subject who experiences desire and for the object of the desire. The boy’s consent, his agency—all seem quite irrelevant. All of the negative assumptions that attach as a matter of course to male sexuality are replaced in the woman by idealizations of motherliness, play, and nurturing.

On the few occasions that female sexual aggression is depicted negatively in artistic renderings, Greer sees it as evidence of a “deep-seated fear of the sexual power of the mother” rather than of any legitimate moral strictures. For example, Greer comments on the story of Potiphar’s wife in the Book of Genesis in the Bible. In that story, Joseph was falsely accused of rape by his employer’s wife after she made sexual advances and he rejected them. Greer never considers the story as a depiction of a common or even potential reality; she sees it as an expression of patriarchal fear and hatred of feminine sexuality: a predictably and boringly feminist interpretation.

Throughout the book, she single-mindedly celebrates what she calls the “age-old collaboration between mature women and boys in search of sexual enlightenment” (p. 125) and refuses to consider that any such arrangement, in any context, could be harmful. It is, of course, impossible to imagine anyone discussing the obverse—older men and pubescent girls—in such unvaryingly positive terms.

Our society is in general far more forgiving of female sexual transgression than of male. It is not unusual for female teachers to be caught sexually assaulting their young male charges and for the incident to be treated with leniency, sometimes even with the suggestion that the boy has had a fortunate, or at least not damaging, sexual introduction. There was a case in Louisiana some years ago, for example, in which Shelley Dufresne, who had had a month-long sexual interaction with a boy of 16 at her school, avoided prison time by taking a plea deal that replaced the original charge of “carnal knowledge of a juvenile” with the lesser charge of “obscenity.” She was 32 years old at the time she accepted the plea deal. This is the climate of tolerance within which Greer was writing. In her celebration of adult women having sex with underage boys, Greer’s book confirms and extends a cultural pattern in which women are allowed a degree of sexual license that men are never offered.

In that sense, The Beautiful Boy is not exactly the bold and pathbreaking book that Greer clearly thought it was, though it does seem to honestly, and perhaps courageously, express Greer’s own views.

Greer’s failure to interrogate the assumption of female innocence—or even to admit that it exists—makes her book far less interesting than it might have been; and our society’s continuing failure to recognize women’s full humanity, including the female capacity for exploitation, reckless indifference, and everyday narcissism, remains a source of gendered inequality that most feminists are happy to accept.

Janice Fiamengo

No comments:

Post a Comment