Many nineteenth-century feminists saw the traditional family as an oppressive institution and looked forward to its destruction.

Contrary to what we now believe, contempt for the traditional family and demands for female sexual liberation didn’t begin in the 1960s. Instead, hatred of the family was firmly rooted in nineteenth century feminist advocacy, which often asserted that marriage, including monogamy and childrearing, was oppressive for women.

Even the acknowledged leader of the mainstream women’s movement in America, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, was a harsh critic of marriage who prophesied its doom; a previously unpublished speech from 1870 reveals her support for free love and her contention that “recognition of the equality of woman with man in all the senses in which it is possible that they should be equal is not enough.”

And she wasn’t the first. From at least the 1840s, anti-marriage and pro-free love advocacy had a toe-hold in America, with its advocates declaring that “Variety is as beautiful and useful in love as in eating and drinking” (Marriage: Its History, Character and Results, 119).

This surprisingly crude statement was written by Mary Gove Nichols (1810-1884), a well-known mid-century women’s advocate, health reformer and proponent of water cures who, along with her husband Thomas Nichols, opened a series of hydrotherapy facilities in New York City. Together, they also published a book in 1854 titled Marriage: Its History, Character, and Results, in which they denounced marriage as a worse evil than slavery, defining it as the “center and soul” of a “system of superstition, bigotry, oppression, and plunder” (88).

Though they contended that both men and women were harmed in marriage, their primary concern, as we might expect, was for women—and this is what is so striking about feminist advocacy regarding marriage in this period: it insisted on the need to liberate women from their alleged subjugation without any acknowledgement of the wider issues of social stability or children’s well-being; of course, men’s needs or interests almost never figured.

In their anti-marriage book, the Nichols alleged that there was no point in advocating for women’s rights while keeping monogamous marriage intact (110) because marriage embodied all the wrongs that women endured. They argued instead for free sexual unions that could be dissolved at will.

The Nichols’ anti-marriage book also made approving reference to the utopian experiment known as the Oneida Community which flourished near Oneida, New York.

|

| Oneida Community, 1848 - 1881 |

Founded in 1848 and in operation until 1881, Oneida was a perfectionist communal society composed of a few hundred members. Practicing Bible Communism, the community held all property in common and outlawed monogamy, mandating instead what the founder called “complex marriage,” a form of free love in which every woman was understood to be the wife of every man, and vice versa.

Natural birth control was practiced through male continence, i.e. sex without orgasm, with younger men initiated into the practice with older (post-menopausal) women; the sexual pleasure and agency of women were affirmed as priorities.

|

| Communal living at the Oneida Community |

The Oneida community was thoroughly socialistic in its practices: children were taken from their parents once they were weaned and were raised by the Children’s Department of the community; sexual jealousy between man and woman; and special bonds between parent and child were prohibited. In their book attacking conventional marriage, Mary and Thomas Nichols quoted a number of Oneida adherents extoling the happiness and freedom they had found there; ironically, Oneida foundered a few decades later at least in part because many of the younger members wanted to practice traditional marriage.

Yet free love remained popular as a feminist ideal, finding perhaps its most vivid expression in Victoria Woodhull, whose name became synonymous with feminist radicalism in the last three decades of the nineteenth century.

Born Victoria Claflin in 1838, Woodhull and her sister Tennie charmed and shocked America in equal measure with their beauty and boldness as advocates for socialism, spiritualism, eugenics, feminism, and free love. From a young age, Victoria had worked as a spiritualist medium in her father’s traveling medicine show,

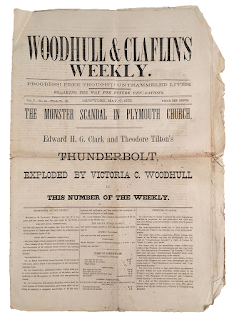

|

| Victoria Woodhull |

After an unsatisfying marriage at age 15 to Channing Woodhull, whose name she kept even after divorcing him and becoming involved with another man, Victoria opened a stockbroking office in New York City with her sister, using money provided by multi-millionaire Cornelius Vanderbilt, one of the sisters’ many admirers; they also ran a tabloid newspaper, called Woodhull and Claflin’s Weekly (1870-76) which was, among other things, the first American paper to print Karl Marx’s Communist Manifesto and also advocated for various progressivist causes.

In addition to accepting the nomination for President of the United States from the Equal Rights Party in 1872, Victoria Woodhull was a much-sought-after public speaker in the 1870s. An admiring audience member (see Cari Carpenter,

introduction to Selected Writings of Victoria Woodhull: Suffrage, Free Love, and Eugenics) reported that 6,000 people crowded into one of her lectures, with an additional 6,000 turned away at the door.Woodhull was not shy about specifying precisely what she meant when she declared herself an adherent of free love—a term which could range in meaning at this time from serial monogamy to polyamory. In her speech “The Principles of Social Freedom,” later reprinted as an essay in a book of her writings, she declared,

“Yes, I am a Free Lover. I have an inalienable, constitutional, and natural right to love whom I may, to love as long or as short a period as I can; to change that love every day if I please, and with that right neither you nor any law you can frame have any right to interfere” (qtd in Selected Writings of Victoria Woodhull: Suffrage, Free Love, and Eugenics, edited and introduced by Cari M. Carpenter).

She extended this argument to include the assertion that sex within a loveless marriage was coercive for women and she supported women’s right to abort pregnancies that resulted from such loveless unions. Her sister claimed in an article in their newspaper that abortion was in fact primarily a problem caused by coerced and loveless sex.

The example of the Claflin sisters shows how frank discussion of taboo subjects was quite possible in the mid-to-later nineteenth century, and also demonstrates how feminists were already at this time mingling calls for female sexual liberation with castigation of men, especially male sexuality, and laments about female victimhood.

Because Victoria Woodhull’s name was a byword for sensationalism for most of her life, the organized American women’s movement was wary of associating too closely with her though she did have friends in the movement. Yet even a cursory glance at the statements of the more respectable of women’s rights advocates shows that they too were attracted by the sexual freedom and rejection of family obligation promised in the theory of free love. Feminist leader Elizabeth Cady Stanton went so far as to declare that free love was the logical and inevitable consequence of the movement for women’s rights.

A recently discovered previously unpublished speech, written in 1870 by Stanton and presented to a private club of both men and women, reveals the full extent of her support for what she called the “natural and free adjustments which the sentiment of love would spontaneously organize for itself.” In case that was not clear enough, Stanton elaborated that she endorsed “nothing short of unlimited freedom of divorce, freedom to institute at the option of the parties new amatory relationships, love put above marriage, and in a word the obnoxious doctrine of Free Love.”

The doctrine was “obnoxious” in 1870, but Stanton firmly believed that the discarding of “legal compulsion” in marriage would emerge in time as the logical outcome of the feminist movement—and that this would be a good thing.

The speech shows Stanton at once clear, even blunt, in recognizing some of the implications of her stance, and notably blind or at least indifferent to others—especially the effects on children, who are not once mentioned.

Early on in the speech, Stanton admitted that marriage would be, if not absolutely demolished, certainly “disturbed” and “abrogated” as a result of her proposal. Allowing “the sentiment of love,” as she called it, to determine human sexual relations would make marriage merely a “legal contract” easily enough dissolved. And Stanton was particularly frank in admitting that her advocacy of sexual liberation had nothing to do with political or social equality and everything to do with a radical conception of personal liberty founded on “freedom from binding obligations.” She asserted that “What is wanted therefore is not merely suffrage and civic rights, and not merely in the second place the social recognition of the equal rank of the sexes, though both of these must be had, but Freedom.”

Stanton began her speech with an extended allusion to couples she has known who have worked for women’s rights together but “neither of whom dared say their souls were their own” (266). This is thought to have been a thinly-veiled criticism of her old friends, and now rivals for leadership of the women’s movement, Lucy Stone and her husband Henry Blackwell. Stone and Blackwell believed in equality, she conceded, but in their relations with each other they were “mutually and equitably the most abject slaves.” She called this “the most subtle form of slavery ever instituted.”

Stanton’s major claim in the speech was that freedom must admit no impediments, including impediments caused by the needs of others. It must be “freedom to repair mistakes, to express the manifoldness of our own natures, and to progress on, to advance to higher planes of development.” Here she did not shy away from enshrining the ever-shifting vagaries of sexual and romantic attraction as the ultimate good of a life. Perhaps in acknowledgement of the radicalism of her argument, she seems to have felt the need to clothe it in a quasi-mystical language of “progress” to “higher planes,” a phrasing directly borrowed from the religious philosophy Theosophy (developed by Russian immigrant Helena Blavatsky) that was popular with many progressive feminists of the time.

In the main part of her argument, Stanton expressed a utopian view of human nature as tending towards virtue and natural order once freed of the man-made laws and social strictures that deform and repress it. The lecture implicitly accused anyone who thought negatively of free love as insufficient in their spiritual and moral fineness. We are to believe that once freed of the deforming chains of custom, human sexual love would flourish in a more perfect form. Stanton conceded that some people would make a bad use of their freedom, but she rejected the conclusion that such bad use would be widespread or damaging.

Notably, Stanton made no mention of the fate of the children of free unions or of partners abandoned by those they loved. She seems not to have considered whether children or the adults themselves would do well within the ever-shifting kaleidoscope of family formations that free unions would produce. It would take another century for the experiment to be tried on a mass scale; but a prescient example is to be found in Henry James’s 1897 novel What Maisie Knew, which explores the selfishness and parental indifference of two divorcing parents and the consequences for their young daughter Maisie.

Many of the elements of our modern feminist culture can be recognized in Stanton and other feminists’ anti-marriage arguments: we see the implicit or explicit pathologizing of male sexuality as an oppressive force that must be controlled, and the celebration of female sexuality as a liberating force to be released; we see resentment against any constraints on women’s freedom and self-determination, including those constraints caused by children, with no corresponding call for male liberation from their constraints or obligations. Birth control and especially abortion as a form of birth control were already being discussed and approved.

Feminists like Stanton and her allies had not yet made the case that women should be free to form and leave any sexual union at will while still being entitled to financial support from the man she had left, but the drift in that direction was already clear—and more on this in future videos. Stanton’s frank expression of faith in free love shows that the destruction of the monogamous family (but not the destruction of women’s legally-enforced right to male support) was part of the feminist agenda from its early days.

Janice Fiamengo

No comments:

Post a Comment