“The Future is Female.” This now-familiar feminist slogan has its roots in the unapologetic female chauvinism of over a century ago.

In 2013, a high-profile public debate took place in Toronto, Canada, part of the popular Munk Debates series. It showcased four women addressing the question “Are Men Obsolete?” Perhaps the fact that no men participated made the result a foregone conclusion—the ‘Yes’ side won easily, though the snide, mostly fact-free exchanges somewhat undermined the claim of the series to canvas “Big Ideas.” Two of the participants, New York Times writer Maureen Dowd and Atlanticmagazine editor Hanna Rosin had already published books glibly asserting male decline (titled respectively Are Men Necessary? and The End of Men). Only one of the participants, dissident academic Camille Paglia, seriously defended men’s continuing civilizational significance.

Such blatant anti-male triumphalism might seem a fairly recent invention, but my research into feminist history shows that claims of female superiority and predictions of women’s imminent ascendency were already common amongst the Anglophone world’s feminist foremothers. This essay provides a few pungent examples of their untrammelled utopianism and cultish obsession with purity.

In 1890 during a congressional committee hearing of the United States Senate on the question of whether women should have the right to vote federally, the American women’s leader Elizabeth Cady Stanton was asked by the committee chairman, Senator Zebulon Vance, about whether women were willing and able to

|

| Zebulon Vance |

Stanton’s answer was the now well-worn holier than thou feminist dodge, “We would decide first whether there should be war,” she told him. “You may be sure, Senator, that the influence of women will be against armed conflicts” (qtd. in Penny Colman, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, 187-188).

To this day, women have shown little ability or desire to prevent armed conflicts or to serve equally with men in wartime. But the promise of a peaceful female utopia has never lost its rhetorical power.

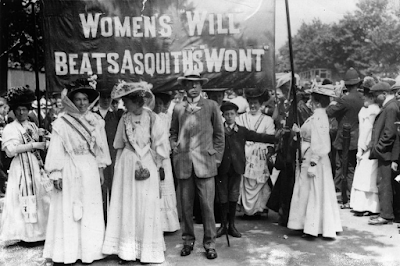

At roughly the same period on the other side of the Atlantic in Britain, the militant suffragettes were similarly prophesying a better world even while they set off bombs and physically attacked members of parliament. In their newspaper The Woman’s Dreadnought, which was published by the East London Federation of the Suffragettes, activist Sylvia Pankhurst waxed eloquent about the altruistic motives that allegedly inspired her compatriots: it was because they wished to “free their

|

| Sylvia Pankhurst |

Keep in mind that she wrote such words in 1915 after a years-long terrorist campaign by her suffragette allies that involved the fire bombing of the homes of members of parliament and, in 1912, an attempted assassination—with a thrown hatchet—of Prime Minister Herbert Asquith. None of the violence—including expensive property damage to individual business owners—was mentioned by Pankhurst when she extolled the boundless compassion of the suffragettes. When asked why, as she delicately put it, they were willing to “defy convention and go to prison,” her answer was that they “defied convention” (i.e. planted bombs) all for good:

“It was because we were sick at heart for the miseries of the people […] because we believed the votelessness of women to be a drag on the wheels of progress” (“We Must Persevere,” in Suffrage and the Pankhursts, ed. Jane Marcus, 278).

It tells us something about the widespread acceptance of the idea of female moral superiority that few feminists felt the need to justify with evidence why female political power would transform the world in the fantastical manner they indicated. In most cases, they simply declared it would, predicting a near-perfect society organized on an infinitely more just, compassionate, and peaceful basis than at present.

|

| Frances Swiney |

In over 300 densely referenced pages, Swiney first outlined the alleged biological basis of female superiority over the physiologically weaker male; then she addressed women’s greater psychological and spiritual advancement over the, as she claimed, near-spiritually dormant male.

At times in the book, she emphasized female complementarity with the male, as when she asserted that “Woman may be called man’s antithesis, yet her functions, joined with man’s, form a perfect whole; neither are complete without the other.”

But such emphasis on complementarity drops away almost entirely from most of the discussion as Swiney rhapsodized about female qualities and achievements at the expense of male, alleging that “The female element preponderates, and will eventually predominate the male” because “the female has laid the foundation of the more solid and lasting attributes, the virtue that alone can be the basis of a higher development” (20).

Swiney enthusiastically approved a statement attributed to the ancient Greek philosopher Socrates that “Woman, made first the equal of man, has now become his superior” (222).

The points of superiority, according to Swiney, were legion. Whether it was women’s more developed bone structure, their greater powers of endurance, their proportionately equal or larger brain size, longer life span, keener physical senses, greater pain tolerance, or more temperate appetites and greater sexual self-control, Swiney was convinced that “The female organism is the one on which Nature has bestowed most care, prevision and attention, and has been, so to speak, her first and her last love” (20). She even jubilated that biological science showed that “Woman is a necessity to man; but man is not necessary to woman” (104). So much for her commitment to complementarity of the sexes.

More importantly than the physical, Swiney argued in detail that feminine qualities of emotion, intuition, and innate morality—largely lacking in men, as she claimed—were necessary to the perfection of humanity. Women were more dutiful and conscientious than men, she argued, and less selfish, less enslaved to physical appetite, and less inclined to pursue pleasure than men, with greater strength of character to bear up under suffering (76). And she went so far as to claim, citing various authorities, that because of these superior moral and spiritual qualities, women held priority “in all the social and industrial development upon which modern civilisation rests” (199), including the development of language, every art form, and much of scientific invention and medical advance.

In time, Swiney predicted, men would learn to adapt themselves to a feminine regime, developing feminine qualities of compassion and self-sacrifice, and learning sexual self-restraint in marriage so that women would not have to bear so many children (237), a practice she believed weakened both women and their offspring. She was certain that it was “acknowledged by men themselves that the Women’s Era is dawning” (296).

Though declaring near the end of the book that “Any impulse that provokes an antagonism between the sexes cannot be too severely deprecated,” Swiney occupied herself for hundreds of pages with damning comparisons between men and women, always to the detriment of men. Men had accomplished little throughout history, she explained, but warfare, bloodshed, and cruelty—yet had thankfully never managed to entirely quell the feminine element. “While men struggled, fought, bled, and died—sometimes, alas! For false ideals […] there was an under-current, deep and unsuspected, that was sapping the foundations of their brutal forces, and clearing the way for the advent of a gentler, purer regime” (218). The insistent emphasis on the purifying of the race physically and morally, familiar from totalitarian leaders in the 20th century, betrays the cult-like origins of feminist ideology.

Swiney did not doubt that woman power would transform the world for good because, as she explained, “Men are content with patching rather than curing; with alleviating a grievance instead of eradicating the cause. As woman takes active participation in political life, her influence will be felt in placing reforms on a far deeper basis.” This was why, as she stressed, “Temporary questions may be decided by man, but the future is in the power of women” (257).

Swiney even made the now-familiar argument that it was the very fact that women had been cruelly oppressed and mistreated for centuries by men that would guarantee women would never oppress others. “Having drunk to the dregs the bitter cup of enforced inferiority, of misrepresentation, of servitude, and humiliation,” women would approve only those political decisions that are “just, true, and thorough” (254).

Reading her consistent calumnies against men makes it hard to believe Swiney’s assurance that, once possessed of equal or greater power than men, women would act with what she called “a sublime forgetfulness of past wrong” as “co-partner” with man (294). The book itself was remarkably short on the alleged womanly quality of “loving and all-enfolding charity” toward men (294).

In a few fascinating short sections, Swiney admitted that women were not yet perfect, and she put her finger on a number of problems in female moral development that might prevent the coming of utopia. Women’s emotionality, she acknowledged, would need to be kept under strict control. The female tendency to sympathize with weakness could lead, if not balanced by rational judgement, to “the grossest injustice to the community at large” as “tenderness degenerates into vicious sentimentality, and compassion for the sufferer into license for the offender” (73).

She also admitted that women had less interest in “community” and “co-operation” than men (81) and were often inclined to frivolity and self-indulgence, with some upper-class women spending their days “in aimless pursuit of some frivolous pleasure or pastime” (85)—an observation that rather weakened her contention about women’s universal oppression. But she was certain that none of women’s defects would not be cured by greater freedoms and higher education; and she gave no thought to the possibility that some of women’s claimed virtues—such as the self-restraint and moral purity she celebrated—would lessen under conditions of greater freedom.

It probably doesn’t need to be said that Swiney would have been shocked and flabbergasted to find herself transported into the 21st century, perhaps into the midst of a contemporary feminist Slut Walk—where women proclaimed their holy right to be as lewd, sexually promiscuous, and provocative as possible, or to see elite women on university campuses screaming and cursing as part of a furious

mob because they had heard an idea that failed to concede to them unlimited power.But in her certainty that “Man recalls the Past, Woman represents the Future” (47), Frances Swiney and many other feminists of her time expressed the chauvinistic arrogance and irrational wishful-thinking that continue to possess feminist leaders of the present day and that inspired a contemptible feminist debate on whether men were obsolete. While declaiming for equality, Swiney, like her feminist comrades, was incapable of a rational assessment of women’s flawed humanity, or of any appropriate recognition of the undeniably male role in civilization. Over a century later, feminist willful blindness has only deepened.

Janice Fiamengo

No comments:

Post a Comment