During the Titanic disaster of 1912, men secured lifeboat seats for women and children, and those men who survived the sinking were grilled in the U.S. Senate about why they weren’t dead. The traditional notion that men owed women protection, and women owed men gratitude, was generally confirmed by the behavior of passengers and crew. The feminist response to the sinking, however, was to deny that women owed men anything, and to express outrage that men had never yet done enough for them.

As we now know, the ship’s bulkhead compartments were constructed in such a manner that water could pour from one bulkhead compartment into another, and this was exactly what happened after the iceberg caused a 300-foot breach in the Titanic’s hull. The inadequate number of lifeboats, and the fact that most lifeboats were launched only about half full during the haphazard evacuation, meant that close to two-thirds of the Titanic’s passengers, the vast majority men, died in the disaster.

The last wireless message of the Titanic reported that the ship was “Sinking by the head. Have cleared boats and filled them with women and children.” Women and Children First was the law of the sea, and many newspaper accounts of the disaster emphasized the stories of individual men who helped others and accepted their own deaths stoically. Many of these stories reported by survivors are almost inconceivably poignant.

Millionaire businessman Benjamin Guggenheim was one. Survivor Rose Icard recorded in a letter how, after assisting with the lifeboats, he “got dressed and put a rose at his buttonhole, to die.”

He sent a message to his wife through his cabin steward Henry Etches, “Tell my wife in New York that I’ve done my best in doing my duty.”

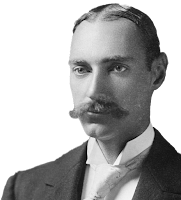

Business

magnate Colonel John Jacob Astor, the richest person on board the

ship and considered one of the richest men in the world, was last

seen on the ship’s deck smoking a cigarette with American mystery

writer Jacques Futrelle. He had just helped his wife, pregnant with

their first child, into the last lifeboat and kissed her goodbye.

John Jacob Astor

It was likely that some or many of the men who died did not wish to perform acts of gallantry. Many knew that they would encounter persistent shaming back home if they managed to get a life-boat seat. Others by nature and by training were dedicated to living out their duty even unto death.

The passenger survival rate told the story (see Wikipedia page). Of first-class passengers, 97% of the women as compared to 33% of the men survived. Of second-class passengers, 86% of the women and only 8% of the men survived; in steerage, the women did less well than other women—with 46% surviving—but still had a significantly higher chance of surviving than the wealthiest and most privileged man. Men in steerage, like all other men, had a low survival rate at 16%. Perhaps notably, children overall fared somewhat less well than the women; though 100% of children in second-class survived, only 83% in first-class and 34% in third-class escaped death. (In total, only 1 in 5 men survived; 3 out of 4 women did.)

For many of those who reflected after the event on the meaning of the Titanic, the age-old verities of self-sacrificing men and protected women seemed obvious; and this element of the Titanic saga has been ably, if somewhat skeptically, reported by Steven Biel in his 1996 book Down With the Old Canoe: A Cultural History of the Titanic Disaster. In this essay, I rely heavily on Biel’s book, which I recommend as a fascinating source of information, though I regret that Biel seemed to find it

necessary to be somewhat sneering in reporting on what he calls Titanic “myths,” including the myth of male chivalry.

As Biel notes, many commentators emphasized the gendered division between those who sacrificed and those who were saved: an editorial for Collier’s magazine argued that the behavior of the men on board showed that there was more to patriarchy than simply the rule of the stronger over the weaker; there was also the duty of care for the weaker: “Power and trust carry with them, in emergencies, the privilege to be self-forgetful and to die” wrote the Collier’s editorialist (qtd in Biel, p. 27).

At

a time when agitation by feminists for the right to vote was

widespread in both England and the United States, many who wrote

editorials or wrote letters to newspaper hoped that the angry

activists were paying attention and drawing the correct lesson, which

was that a benevolent patriarchy protected women, and secured their

interests, far more effectively than the mere right to vote ever

could. The editors of the Baltimore Sun emphasized that "The

action of the men on the Titanic was not exceptional. But it must be

recognized as an act of supreme heroism, and as showing that women

can appeal to a higher law than that of the ballot for justice, consideration, and protection" (quoted in Biel, p.30).

Steven Biel

Other commentators asked the question that has never, to my knowledge, been honestly and satisfactorily answered by any feminist: if equality means equal suffering and death at times of crisis—which it must do, if it is really equality—then do women want equality? And if women do not want that kind of equality, why do they repeatedly pretend they do?

One letter writer calling himself Mere Man asked the question: “Would the suffragette have stood on that deck for women’s rights or for women’s privileges?” Reverend W.S. Plumer Bryan drew a similar conclusion for feminists: “The women who are demanding political rights may well take care, lest they lose what is infinitely dearer,” he warned. “If men and women are to be rivals, can she expect such chivalrous protection as the women of the Titanic received?” (qtd in Biel, p. 31).

Members of the National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage pointed out that the women who went into the lifeboats, whatever they might say about equality in other contexts, were not feminists:

"[…] When the final crash came men and women alike were unanimous in making the sex distinction. It was not a question of “Voters first,” but the cry all over the ship was “Women first!” In acquiescing to that cry, the women admitted that they were not fitted for men’s tasks. They did not think of the boasted ‘equality’ in all things. This is not an implication that women were inferior, it just shows an inequality or a difference. (qtd. in Biel, p. 32).

Immediately after the disaster, many women wanted to express their gratitude for male protectiveness. Within a few weeks, the Women’s Titanic Memorial Fund was organized by American women to build a monument in tribute to manhood; it raised half a million dollars through donations, including from Titanic survivor Mrs. Archibald Forbes, who had played bridge with John Jacob Astor on the night of the sinking.

Featuring a statue sculpted by John Horrigan, the Women’s Titanic Memorial was unveiled in 1931 and now stands in Washington, DC.

The monument is dedicated “To the brave men who perished in the wreck of the Titanic April 15, 1912. They gave their lives that women and children might be saved.” An editorial described it as a monument “from the weaker to the stronger, from the grateful to the gallant, from the saved to the saver of life” (qtd. in Biel, p. 37).

Not surprisingly, however, not all women of the time expressed gratitude towards men, and many refused even to modify their anti-male denunciations in the days and weeks following the wreck. One letter writer didn’t like the fact that the Women’s Titanic Memorial Fund was dedicated to male heroes, asking “Why not, instead of having the memorial solely for the heroes of the wreck, have it also for the heroines!” She had missed the point that it was only men who had died, and died in such numbers, because of their sex and for women and children (qtd. in Biel, p. 54).

Another woman simply refused to accept that men had behaved heroically, asserting in a letter to the Baltimore Sun that much if not all of the alleged heroism “was due to the belief in the unsinkable qualities of the ship” or to the part “pistols played in converting cowards into brave men” (qtd in Biel, p. 107). It wasn’t enough for her that the men were dead; it was necessary for her to deflate the praise being offered, emphasizing either male ignorance or compulsion.

|

| Alice Blackwell |

Alice Stone Blackwell, editor of the North American Woman Suffrage Association’s publication, the Woman’s Journal, acknowledged that some men had acted chivalrously but called for a “new chivalry” — allegedly a chivalry for all — that could only come about when women had political power because true chivalry was a characteristic of women rather than men (qtd. in Biel, p. 104). She made her claim by focusing solely on the suffering of women and girls:

“The chivalry shown to a few hundred women on the Titanic,” she wrote, “does not alter the fact that in New York City 150,000 people—largely women and children—have to sleep in dark rooms with no windows; that in a single large city 5,000 white slaves [prostitutes] die every year; that the lives and health of thousands of women and children are sacrificed continually through their exploitation in mills, workshops and factories. These things are facts.”

As feminist always do, she quickly diverted attention from an actual instance of extraordinary male generosity to an alleged instance of male indifference, focusing solely on the suffering of poor women and girls, ignoring or denying that of boys and men who certainly suffered at least equally as a result of poverty, industrial exploitation, and unhealthy living and working conditions. Her claim that women were more generally chivalrous than men was contradicted in her failure to consider any of the ways that men and boys also needed help.

Other commentators used a different but equally standard feminist tactic in blaming men for the Titanic accident, claiming that it was men’s fault the ship had sunk and alleging that once women had more power, accidents at sea would rapidly diminish or cease altogether.

Agnes

Ryan wrote for the afore-mentioned Woman’s Journal that

“Wholesale, life-taking disasters must almost be expected” as

long as “the laws and the enforcement of the laws are entirely in

men’s hands.” She was convinced that “the Votes for Women

movement seeks to bring humanness [and] the valuation of human life,

into the commerce and transportation and business of the world and establish things on a new basis, a basis in which the unit of measurement is life, nothing but life!” Women cared about life, allegedly, men only about money.

Agnes Ryan

The previously mentioned Alice Blackwell sounded the same fantastical note, asserting that “There was no need that a single life should have been lost upon the Titanic” and claiming that “There will be far fewer lost by preventable accidents, either on land or sea, when the mothers of men have the right to vote” (qtd in Biel, p. 105).

Exploiting this absurd argument based on collective blame and female salvation, some feminists thought sacrificing themselves for the women was the least the men could have done. “After all,” wrote one letter writer, “the women on the boat were not responsible for the disaster,” so it was only right that men should reap the rewards of male cupidity and irresponsibility (qtd in Biel, p. 107).

|

| Emma Goldman |

|

| Isidore and Ida Strauss |

There is something uncomfortable in moralizing about the Titanic or about any instance of male sacrifice. Undoubtedly most of us would wish to live in a society where no one is forced to make such choices or to prove their worthiness by dying—as only men ever must do. But the awkward question does arise: do feminists advocate equality in self-sacrifice? Would the feminists refuse the lifeboats? And having accepted the metaphorical lifeboat that modern society offers women, how much longer can feminists continue in their refusal of gratitude and insistence on male privilege? Too many modern feminists sound exactly like those who thought that dying to save women was the very least the men could do.

Janice Fiamengo

No comments:

Post a Comment