Let us go even further back in feminist history to the late eighteenth century and the writing of Mary Wollstonecraft, an acclaimed proponent of women’s rights, whose 1792 treatise, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, is now widely regarded as the founding document of Anglophone feminism. As I will hope to show, Wollstonecraft’s commitment to the Enlightenment principles of equality and reason is at best skin deep, covering over a foundation of anti-male double standards and irrational hostility that forecast all too clearly the next 230 years of female supremacism.

.png) |

| Mary Wollstonecraft |

In the essay, Wollstonecraft partially agreed with and partially objected to those authors of conduct books and other writings who claimed that women’s main purpose in life was to be a companion to men. Yes, women were men’s companions, Wollstonecraft assented, but they could be so only when they were men’s equals.

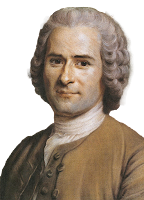

|

| Jean-Jacques Rousseau |

The problem with 18th century society, according to Wollstonecraft, was that women were in general taught to be attractive rather than good and wise. “The whole tenor of female education tends to render the best disposed romantic and inconstant; and the remainder vain and mean” (A Vindication, p. 79).

Men made women like this, Wollstonecraft asserted, because men failed to understand women or respect them, “more anxious to make [women] alluring mistresses than affectionate wives and rational mothers” (A Vindication, p. 6). As a result, “The sex [that is, woman] has been so bubbled by this specious homage, that the civilized women of the present century, with a few exceptions, are only anxious to inspire love, when they ought to cherish a nobler ambition, and by their abilities and virtues exact respect” (p. 6). Wollstonecraft further declared that “To be a good mother, a woman must have sense and that independence of mind which few women possess who are taught to depend entirely on their husbands” (A Vindication, p. 160). The progress of civilization itself, according to Wollstonecraft, depended on the proper education of women.

Who could object to women cherishing noble ambitions and becoming worthy of men’s respect, especially as “affectionate wives” and “rational mothers”? Wollstonecraft famously argued for the co-education of women and men on the basis that only when women were equipped with intellectual and economic self-reliance would they be able to truly fulfill their domestic roles: “If marriage be the cement of society, mankind should all be educated after the same model, or the intercourse of the sexes will never deserve the name of fellowship, nor will women ever fulfil the peculiar duties of their sex, till they become enlightened citizens, till they become free by being enabled to earn their own subsistence, independent of men […]” (A Vindication, p. 175).

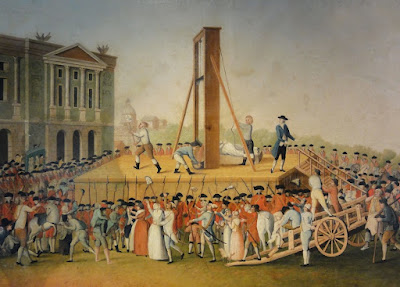

So far, this is all perfectly reasonable, with the rather large problem that Wollstonecraft never did address the significant tensions between what she called the “peculiar duties” of womanhood (in other words, women’s particular role in the family) and the very different masculine roles of public service, political life, academic study and the conduct of business and the professions that she believed should be opened to women. This tension would become one of the major unresolved, and perhaps unresolvable, conundrums of feminist ideology, justifying more and more convoluted demands and allegations in the name of equality; a little more on this later. Yet even Wollstonecraft’s lofty statements about rational education for virtue were buttressed by assumptions far less amenable to reason, not unlike how the commitment by the proponents of the French Revolution to liberty, equality, and fraternity ultimately coexisted with mass repression and violence.

In contrast to Burke’s anti-revolutionary defense of custom and tradition, Wollstonecraft’s vision was radical and utopian, looking to France as a blueprint for the future. Her feminism was possibly influenced, though this is not a certainty, by French feminist Olympe de Gouges, who had published in 1791 a pamphlet called the Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen, which criticized the failure of the Revolution to liberate women.

De Gouges’s feminism was caustic and condemnatory, describing men as “Bizarre, blind, bloated with science and degenerated […] into the crassest ignorance” (p. 1) and declaring in Article 4 of her Declaration that nothing but “perpetual male tyranny” had kept women from their natural rights (p. 2).

Wollstonecraft was so deeply interested in the transformation of society and female democratic participation that she went to Paris in late 1792 just as the Revolution was entering its most violent and vengeful phase.

Only months after Wollstonecraft arrived in France, the radical Jacobins seized control of the government, determined to eliminate so-called counter-revolutionary forces, which they did by executing at least 17,000 people during the year-long Reign of Terror (not counting the many who died in prison).

Wollstonecraft, who had allied herself mainly with the more moderate Gironidists, saw friends executed, including Olympe de Gouges, as it happened, and was herself saved from the guillotine by her romantic liaison with the American businessman and diplomat Gilbert Imlay, who registered her with the French authorities as his wife, thus securing her safety as an American.

|

| Gilbert Imlay |

Though they didn’t marry, Wollstonecraft fell in love with Imlay and had a child with him; and after he left her, she twice attempted suicide.

Through her turbulent time in France, Wollstonecraft experienced the devastation wrought by revolutionary fervor both personally and politically; years later the costs of Romantic idealism would be lived out in the life stories of her two daughters, Fanny Imlay and Mary Shelley, author of Frankenstein.

Yet Wollstonecraft’s commitment to the radical revisioning of society was never extinguished; her 1794 book An Historical and Moral View of the French Revolution defended the aims and significance of the revolution despite the many thousands of innocent lives it had destroyed.

A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, written before she went to France, demonstrates Wollstonecraft’s enduring belief that happiness could be achieved by changing society and changing human nature itself; such utopianism, as we’ll see, rested on double standards about male and female behavior that were neither admitted nor justified in the work; and which are now the all-too familiar foundation of feminist ideology.

Wollstonecraft admitted in her book that many women were unintellectual, interested mainly in making themselves attractive and angling for a powerful husband. But she insisted that these were not women’s natural capacities but were rather the signs of their bondage.

“The education of women has, of late, been more attended to than formerly, yet they are still reckoned a frivolous sex, and ridiculed or pitied by the writers who endeavour by satire or instruction to improve them. It is acknowledged that they spend many of the first years of their lives in acquiring a smattering of accomplishments; meanwhile strength of body and mind are sacrificed to libertine notions of beauty, to the desire of establishing themselves—the only way women can rise in the world—by marriage” (Wollstonecraft, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, p. 9).

Wollstonecraft even went so far as to allege that women’s abuse of power was really proof of the weakened state in which they were unfairly kept, which alone caused them to develop “cunning” and “a propensity to tyrannize” (A Vindication, p. 10).

Some feminists have been disappointed in Wollstonecraft for not directly asserting the intellectual equality of women with men. However, what Wollstonecraft lacked in insistence on equality, she more than made up for in man-blaming. Confessing to have avoided “any direct comparison of the two sexes collectively, or frankly acknowledging the inferiority of woman, according to the present appearance of things,” she emphasized that, “I shall only insist that men have increased that inferiority till women are almost sunk below the standard of rational creatures. Let their faculties have room to unfold, and their virtues to gain strength, and then determine where the whole sex must stand in the intellectual scale” (A Vindication, p. 35).

Elaborating what would become in the 20th century the theory of social constructionism, Wollstonecraft implied that it was impossible to say at the present time what woman might be and do if only given the chance.

Whatever defects women showed at present were first and foremost caused, she explained, by the unjust and irrational expectations of men:

“Why do men halt between two opinions, and expect impossibilities?” she asked, “Why do they expect virtue from a slave, from a being whom the constitution of civil society has rendered weak, if not vicious?” She went on to predict that it would take a long time to change social prejudices: “It will also require some time to convince women that they act contrary to their real interest on an enlarged scale, when they cherish or affect weakness under the name of delicacy, and to convince the world that the poisoned source of female vices and follies […] has been the sensual homage paid to beauty:- to beauty of features; for it has been shrewdly observed by a German writer, that a pretty woman, as an object of desire, is generally allowed to be so by men of all descriptions; whilst a fine woman, who inspires more sublime emotions by displaying intellectual beauty, may be overlooked or observed with indifference, by those men who find their happiness in the gratification of their appetites” (A Vindication, p. 49).

Who could blame women, Wollstonecraft stressed in the above passage, for wanting to be beautiful and for not caring about virtue when men uniformly celebrated beauty and often ignored or even slighted virtue? Here Wollstonecraft came close to fundamental matters in the nature of male and female desire, but she fatally weakened her argument by giving the most damning interpretation possible of men’s actions and by excusing women from any accountability. According to Wollstonecraft, there was in men’s attraction to beautiful young women nothing healthy and nothing benign. It was merely “sensual,” a gross physical appetite.

As in nearly all future feminist analyses of the relationship between men and women, Wollstonecraft depicted women as reacting to a situation entirely created by men for men that they, women, had played no role in supporting. Whether women tended to prefer certain qualities in the men they married—Wollstonecraft wouldn’t say and didn’t care. So focused was she on identifying how men turned women into “slaves,” as she repeatedly called them, that she refused to recognize any form of female agency or limitations on male freedom.

Even clear demonstrations of female sexual power were interpreted by Wollstonecraft as evidence of their degradation.

“I lament that women are systematically degraded by receiving the trivial attentions, which men think it manly to pay to the sex, when, in fact, they are insultingly supporting their own superiority. It is not condescension to bow to an inferior. So ludicrous, in fact, do these ceremonies appear to me, that I scarcely am able to govern my muscles, when I see a man start with eager, and serious solicitude, to lift a handkerchief, or shut a door, when the lady could have done it herself, had she only moved a pace or two” (A Vindication, p. 60).

Indeed, the woman could have done it herself, but didn’t. Is the man truly degrading the woman when he performs actions of obeisance for her? Wollstonecraft’s argument refused to recognize male need, solicitude, or protectiveness because these would complicate the stark picture she was painting.

Wollstonecraft continually mocked the idea that women wanted or needed male protection, or that such protection ever came as a benefit to women or at a real cost to men themselves: “In the most trifling dangers, they [women] cling to their [male] support with parasitical tenacity, piteously demanding succour; and their natural protector extends his arm, or lifts up his voice, to guard the lovely trembler—from what? Perhaps the frown of an old cow, or the jump of a mouse” (A Vindication, p. 65).

Were women, then, for their own moral good, to be left defenceless in cases of actual danger—a charging bull, a venomous snake, or a sinking ship?

Wollstonecraft ignored such a question, focusing instead on minor acts of gallantry that she regarded as sexist insults. “When a man squeezes the hand of a pretty woman, handing her to a carriage, whom he has never seen before, she will consider such an impertinent freedom in the light of an insult, if she have any true delicacy, instead of being flattered by this unmeaning homage to beauty” (A Vindication, p. 104). In Wollstonecraft’s view—what became the standard feminist view of so-called “benevolent sexism”—all male expressions of attraction to women were merely means to subordinate them.

Like many feminists who came after, Wollstonecraft envisioned a fantastical redeemed world in which the passions of both sexes would be reformed, divorced from any bedrock in human nature—a nature that Wollstonecraft, in line with other Lockean philosophers of her time, saw as highly malleable. In her utopian realm, men would cease to be attracted by a woman’s physical beauty and women would cease to be pleased by male deference or attracted to male power; she even went so far as to allege that once possessing their own abilities in the educational and professional spheres, women would never exploit their sexuality or tryst with “rakish” men (p. 124). Wollstonecraft’s own self-destructive romantic choices—of the American adventurer Gilbert Imlay, and before him of the already-married Swiss artist Henry Fuseli—did not seem to have been lessened by her highly developed

intellectuality or financial independence. But like most feminists, she could not or would not look squarely at how her wayward and passionate impulses contradicted her idealized imaginings of female rectitude.

|

| Henry Fuseli |

intellectuality or financial independence. But like most feminists, she could not or would not look squarely at how her wayward and passionate impulses contradicted her idealized imaginings of female rectitude.

She believed in the potential of radical ideas to reform the world, even that ideas could cure women of such faults as romanticism and infidelity: “Were women more rationally educated, could they take a more comprehensive view of things, they would be contented to love but once in their lives; and after marriage calmly let passion subside into friendship” (A Vindication, p. 125).

As if this denial of female nature were not outlandish enough, Wollstonecraft even made the argument that when women were independent from men, they would be more affectionate and faithful. “Would men but generously snap our chains, and be content with rational fellowship instead of slavish obedience, they would find us more observant daughters, more affectionate sisters, more faithful wives, more reasonable mothers—in a word, better citizens. We should then love them with true affection, because we should learn to respect ourselves” (A Vindication, p. 158). Notably, Wollstonecraft did not explain how independence and opportunity would make women more rather than less content in their domestic duties, or more inclined to be affectionate and faithful to the beings she had characterized throughout her treatise as bigoted and exploitative. Men were simply to accept Wollstonecraft’s undefended pledge. “Make [women] free and they will quickly become wise and virtuous” (A Vindication, p. 186).

The only point on which Wollstonecraft’s treatise does not predict later feminism is in her insistence that education should inculcate in women the domestic virtues of marital fidelity, motherhood, companionability, responsibility for raising children, and care of the household; all of these drop away almost entirely from later feminist discussions.

But exactly what virtue would look like in women and how it would be encouraged or enforced are left conveniently vague in Wollstonecraft’s treatise, which seemed unwilling to admit that greater freedom alone would not improve women’s characters.

Wollstonecraft was not prepared to consider that women were at least as likely as men to abuse power, especially if they could do so under cover of the innocent victimhood that Wollstonecraft and many others so assiduously promoted. “Depressed from their cradles” (p. 201) as Wollstonecraft claimed women were, they could not be held responsible for their failures or bad actions. 230 years later, with women vastly outnumbering men at Anglophone universities and outpacing men in many areas of employment, we are still waiting for the time so long deferred when the moment of women’s moral accounting will at last arrive.

Janice Fiamengo

No comments:

Post a Comment