In his 1913 book The Fraud of Feminism, British barrister Ernest Belfort Bax described, with his characteristic wit, how “Female criminals are surrounded by a halo of injured innocence,” “convinced of the maliciousness of [their] accusers” and of their own lack of responsibility (p. 51-52). In fact, the historical record demonstrates a self-reinforcing pattern in which legal authorities and public opinion often excused rather than punished women’s bad actions, with the result that some women come to believe that in many circumstances they have the right to kill.

|

| Sonja Starr |

|

| E. Belfort Bax |

Studies demonstrate that criminal law was made by men for men and had difficulty conceiving of and punishing female deviance. Where there was any doubt as to a woman’s guilt, juries were extremely reluctant to convict; and even where there was no reasonable doubt, juries were eager to find mitigating circumstances such as temporary insanity, abuse, or male coercion to justify lightened sentences or acquittal.

In the past two essays, we looked at examples of elaborate excuse-making for female killers in the United States; we turn today to Ireland and Britain to examine large-scale sentencing patterns.

Professor of Social Policy Pauline Prior published a 2005 study on insanity defences used in Ireland between 1850 and 1900, and found that an extremely high number of women who killed their children were acquitted in that manner.

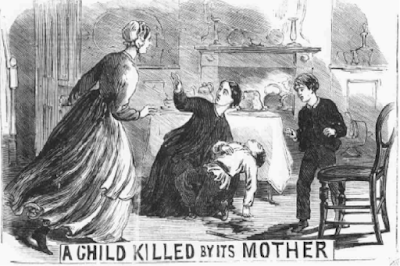

Prior explains that “Infanticide—though officially outlawed in Ireland, as in many other countries—was not unusual in the nineteenth century” and that “Attitudes to infanticide were highly ambivalent” (p. 2) as shown by the very low rate of reporting of the crime to authorities. It has been estimated that “61 percent of all homicide victims in England in the mid-nineteenth century were under the age of one year” (Prior, p. 5), almost all of them killed by women.

Many of the murdering mothers sent to Dundrum Asylum in Ireland spent only a few years there or even less before being discharged.

These included Margaret Rainey, a nineteen-year-old woman who in 1891 was found not capable to stand trial after she threw her newborn baby out of a window, claiming afterward that the baby had been stolen away, and who was discharged into the care of her sister after spending close to three years at the asylum (Prior, p. 2). Hannah Sullivan was a seventeen-year-old girl who in 1895 killed her baby by cutting off the baby’s head, and who, while showing no signs of insanity at Dundrum, was discharged to her mother’s care just one year later (Prior, p. 3). Many other such cases testify to the willingness—even eagerness—of juries to believe in the temporary insanity of mother-murderers.

Comments by mental health authorities made clear that such women, especially if they were unwed mothers, were seen as victims of circumstance—and of male seducers—to be pitied rather than held responsible: “Great commiseration is, no doubt, due,” wrote one asylum inspector, “for we can fully imagine how shame and anguish must weigh on an unfortunate and betrayed female […] and what strong temptations induce her to evade the censure of the world […] by a crime that outrages her most powerful instinct, maternal love of offspring” (qtd in Prior, p. 3). Notably, this authority did not hesitate to assert that a woman’s “most powerful instinct” was “maternal love,” even in cases where the alleged instinct had clearly failed to manifest or, if operative, had been brutally overridden. The circular reasoning of the insanity defence held that a mother’s murderousness did not disprove maternal instinct; rather, the non-operative maternal instinct proved insanity.

The aforementioned inspector was also typical in stressing the pain of women “betrayed” by men and shamed by a judgemental society. But what of the substantial number of married women who killed their children? The author of the article notes that these were also frequently acquitted with an insanity plea. Prior describes the case of Sarah McAlister, a thirty-three-year-old married woman who in 1892 murdered with poison the youngest two of her six children, and Catherine Wynn, a thirty-five-year old married woman who in 1893 drowned her three children in a bath of boiling water (Prior, p. 4). Despite or perhaps because of the deliberation involved in these multiple killings, juries chose to view the perpetrators as unwell rather than cruel.

But an insanity defense was not the only route to leniency. Prior reports that of the child-murderers who did not use an insanity plea, the vast majority received lessened sentences for their killings, with time spent in prison ranging between three and fifteen years.

The tendency to excuse women even when they committed crimes requiring ferocity and ruthlessness meant that women who killed adult men and women were also far less likely than men to be indicted, more often acquitted, and if found guilty, convicted of a lesser crime. History Professor Kathy Callahan, in a 2013 article “Women Who Kill,” analyzed the records of felony cases at London’s Old Bailey courthouse in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, finding that English society during this period had relatively little interest in punishing women for their violence. She notes that “Society did not feel threatened by female transgressions” (Callahan, p. 1015) and confirms criminal law expert Gregory Durston’s work on female criminals in the 18th century, which found that “Females were not held to the same standards of indictment and conviction as were males” (qtd in Callahan, p. 1016).

In her study of Old Bailey records, Callahan found that in trials for violent crime, juries acquitted 61 percent of female defendants. Most indictments for murder were downgraded to manslaughter, and especially in cases where the perpetrators killed husbands or lovers, the women’s claims that they had been previously abused by their victims often gave the jury reason to recommend clemency.Callahan cites the case of Jane Churn, for example, who was found guilty of manslaughter after she fought with her lover, James Scofield. Churn stabbed her victim Scofield with a fork, then followed him down the stairs, where he fell, upon which she beat him to death with a poker. For this offence, she was fined the amount of one shilling, receiving this extremely light sentence because the jury believed her that the victim had started the altercation and that Churn had been in the position of fighting back (p. 1026).

To demonstrate the highly sympathetic disposition of courts toward female killers, Callahan quotes a judge charging a jury in another case in which a woman killed her lover during an altercation. The judge made clear in his instructions that if the male victim was believed to have been violent to the woman beforehand, then “manslaughter” was the limit of the charge:

He said to them: “If you should be of opinion any such scuffle happened between them, and in fact that there was enmity between him and this woman, and the story to be true, and that he had been beating her before—if you believe that to be the case, and that this woman under these circumstances committed this act of violence, although perhaps she might have gone further than she ought to have gone […], the law in that case extends the crime to manslaughter only.” (qtd in Callahan, p. 1026)

Such reasoning amounted to a near-automatic exemption from capital punishment for female killers of men, who could often plausibly argue either that they had acted in self-defence or that they had been provoked by their lover’s abuse. As E. Belfort Bax declared, “A man murdered by a woman is always the horrid brute, while the woman murdered by the man is just as surely the angelic victim” (Bax, The Fraud of Feminism, p. 47). Juries were in general willing to believe women’s claims to have acted only in response to harsh treatment.

Moreover, juries were also willing to believe that when men and women acted together in a violent crime, the man was the one on whom the more severe punishment should fall, based on the common belief that women were often coerced or led into criminal violence by men.

In one example cited by Callahan, Sarah Brown was a prostitute who was accused of killing a stranger on the street who bumped into her and her friend, Antonio Cordosa. Brown, the woman, received a light sentence of one year in jail, while Cordosa was punished with the harshest sentence possible: death by hanging, followed by anatomization and dissection after death, with his opened body displayed to the public (Callahan, p. 1026).

Callahan emphasizes that when women were accused alongside men, the principle of coercion was regularly applied to lessen the woman’s responsibility, which allowed many women to escape the death penalty for murder.

In her conclusion to the study, Callahan cites V.A.C. Gatrell in his study of criminal execution in England The Hanging Tree, which argued that from 1770-1868, “The weaker sex became a vehicle through which men registered their potency, benevolence, and chivalric selves” (Gatrell, qtd in Callahan, p. 125). The feminist-compliant phrasing implies that women, being subordinate to men, were made a mere “vehicle” through which masculine agency was enacted. When stripped of feminist terminology, however, the plain truth in Gatrell’s statement is that the tendency of the law to hold women less guilty meant that women were punished less harshly, or not at all, for even very violent crime.

Callahan’s elaboration of Gatrell’s

point is also worth pondering, revealing as it does her approving

interpretation of the courts’ leniency. She writes, “The

reduction of many murder charges to manslaughter indicates that

judges and juries understood that women led lives constrained by

societal norms […] and that sometimes emotional responses to

difficult circumstances led to disaster. In this way, the courts

demonstrated ‘benevolence and chivalry’ as well as their

willingness to sanction violence carried out by these women,

recognizing that sometimes life left many of them with few options

but to defend themselves in ways men would” (Callahan, p. 1030).

Callahan’s sentimental phrasing of what judges and juries allegedly

“understood” about women’s lives demonstrates that she, like

them, believed that women’s constrained lives and difficult

circumstances often left them with little choice but to kill. Notice

how she not-so-subtly redefines women’s killing as necessary self

defense. These women may have killed like men, as she put it,

but they weren’t punished like men.

Kathy Callahan

Here is the “halo of injured innocence” referred to by E. Belfort Bax, the belief that women were often justified in their violence and deserving of sympathy, not condemnation. Bax found it a startling fact that “Women when most patently and obviously guilty of vile and criminal actions will, with the most complete nonchalance, insist that they are in the right” (The Fraud of Feminism, p. 52), and he mentioned with disgust that “We hear and read, ad nauseum, of excuses […] for every crime committed by a woman, while a crime of precisely similar a character and under precisely similar circumstances, where a man is the perpetrator, meets with nothing but virulent execration from […] British public opinion” (The Fraud of Feminism, p. 54).

Bax’s contentions and the findings of modern researchers give the lie to the pendulum swing theory of gendered history, the idea that because women were harshly treated in the past, they are somewhat justified in demanding special privileges today and in treating men badly in their turn. The fact is that, at least for the past 200 years, women have exercised female privilege under law even to the extent of escaping standard punishment for murder, and have done so under the belief that they deserve such preferential treatment.

It is long past time our society considered the consequences of such leniency on women. What but diminished moral capacity—or even a completely warped morality—can result from such sustained excuse-making? If feminists and others truly believe women morally equal to men, perhaps we should at long last be willing to recognize, name, and hold women accountable for their violence.

Janice Fiamengo

No comments:

Post a Comment